Vast forests covered northern Minnesota 150 years ago. Giant white pines often rose 200 feet and were six feet in diameter. Some of the stands had been growing since 1500 A.D. When Minnesota became a state, more than half its land was in deep shade. For centuries this area, more than 31 million acres of forest, provided food and shelter to the Native Americans who migrated there.

In the 1800s, as European settlers moved in, they viewed the trees as raw material to help build the country. The forests of white pine in the eastern United States had been depleted by loggers to burn as fuel and to build furniture, houses, ships, bridges, and boardwalks. So lumbermen moved west to supply a growing nation. People saw the huge stands of white pine in Minnesota and thought they were inexhaustible.

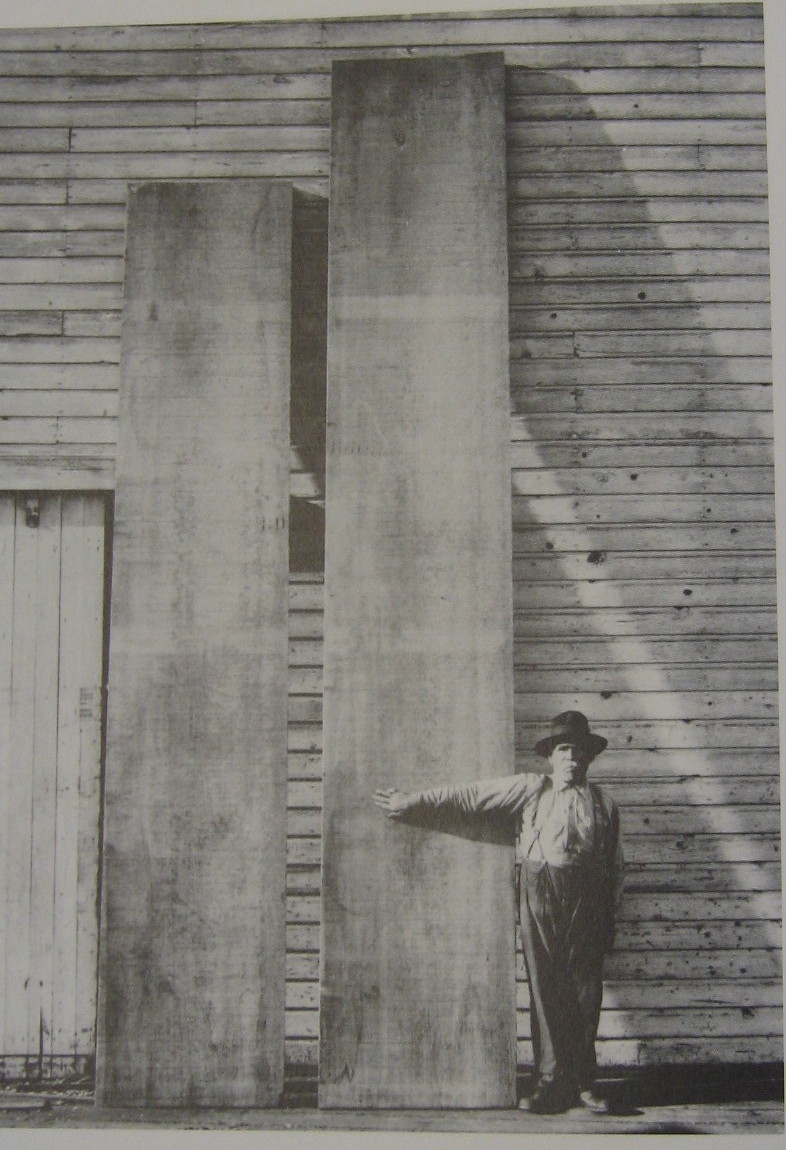

White pine with its straight trunk and large size was the prize of trees. It was easy to cut (like “slicing cheese”) and produced huge, knot-free boards. It was strong and durable and resistant to decay. Loggers liked the tree because it could be processed in a mill as much as a year after felling and was still useful. By contrast, hard woods needed to be processed immediately after being cut down or large cracks would develop making the wood useless. Also pine logs were more buoyant than other trees and could easily float down waterways to the mills.

Lumbermen first entered Minnesota along the St. Croix, Rum, and Mississippi rivers on land ceded by the 1837 treaty between the U.S. government and the Ojibwa Indians. A group of New England businessmen started the first commercial sawmill at Marine on the St. Croix in 1839. The next year a second sawmill was built in Stillwater. Soon after, mills popped up along the rivers, and the boom had begun.

The early mills were crude, operated by waterpower, and production was slow. But when steam power and efficient saws were developed and draft horses replaced oxen, pine logs moved ever faster from the forest to the sawmills. As wood was depleted in one area, lumbermen moved to more plentiful lands around the state. By 1870 there were more than 200 lumber mills in Minnesota, employing thousands of workers. Soon railroads replaced river transport, and production sped up again. By 1899 Minneapolis was the leading lumber producer in the world, producing nearly 600 million board feet that year.

When Minnesota was at the peak of production—1900-1910—there were 20,000 loggers, 20,000 workers in the mills, and 20,000 more in wood production factories. The state’s yield in 1900 was 2.3 billion board feet of lumber, enough to construct a 9-foot-wide boardwalk to encircle the earth at the equator!!

By 1920 the inexhaustible forest did not seem so endless. The yield was down to 576 million board feet that year, and lumbermen looked to the Pacific Northwest with its enormous expanses of Douglas fir. In 1937 when the large sawmill in International Falls closed its doors, the era of big white pine logging was at an end. But during its reign, that industry had produced more than 67 billion board feet of lumber!

| Year | Acres Dominated By White Pine Forest | Percent Remaining |

|---|---|---|

| 1837 | 3,500,000 | 100% |

| 1936 | 224,000 | 6% |

| 1962 | 135,800 | 4% |

| 1990 | 67,500 | 2%* |

*Mostly second forest growth (60-120 years old)

The boom made cities of Minneapolis, Saint Paul, and Duluth and made Minnesota a prosperous industrial state. But the logging left a barren landscape in Minnesota’s north country. Lumbermen wanted the trunk of the tree, not the tops or the branches. That was left as slash. As a result, many destructive fires swept through the area.

Logging continued at a reduced pace throughout the century and continues today. When cutting began (1837) 3,500,000 acres of Minnesota forests were dominated by white pine. By 1990, 98% of Minnesota white pine was gone, leaving 67,000 acres which included pine, most of it young growth. The decline has been greater here than elsewhere in the nation. For example, Minnesota originally had twice the white pine acreage of New Hampshire, but now has less than a 20th as much.

Recently the logging industry has adopted much more sustainable practices. White pine is no longer the primary tree cut as timber: oak and aspen are also desirable. In addition, the law requires that trees cut down must be replaced with new seedlings.

Regeneration and Restoration Efforts

Many Minnesotans watched the continual harvest of white pine during the peak years and worked to spare large sections of land. Itasca State Park was established in 1891; Chippewa National Forest, in 1892. The state created a Forestry Board in 1896 and a Conservation Commission in 1925. The Wilderness Act of 1964 set aside the area now designated as the BWCA, a wilderness of 1,090,000 acres.

Individuals, conservation groups, and government agencies have spearheaded a variety of re-planting schemes over the years. All of these have been of benefit to the white pine inventory. Yet most have been hampered by a number of factors. White pine blister rust was introduced on seedlings from Europe in the early 1900s and remains a problem. The large deer and rabbit populations in Minnesota graze on young white pines, killing many. In addition, white pine seeds require disturbed soil to germinate. Forest fires and tilling are two ways this need can be supplied. Now much of the land that was once forested is either developed or farm land, limiting the areas available for trees to establish themselves.

In addition the slow growing trees need sunlight to thrive. Hardwood trees and undergrowth prevent this, so white pine has trouble producing new plants in densely vegetated areas. And finally, reforestation is an expensive task. The cost for the year 2000, as outlined in “Tree Crops for Marginal Farmland: White Pine, with Financial Analysis” estimated that planting and maintaining one acre of white pine forest was approximately $240.

Today the state of Minnesota, local government, industry leaders, and individuals have a number of programs in place that are making good progress in restoring the native ecosystem of white and red pines. By 2009, the DNR had planted 800,000 white pine seedlings on state lands. In Bemidji, the Red Lake Band of Ojibwa is replanting 50,000 acres of tribal land that was misused in the 1990s. Their goal is to reforest about 1,000 acres annually for the next fifty years.

Many smaller efforts, like the Break A Bat, Plant a Tree Twins baseball team partnership with the DNR, provide a significant number of new plantings each year. Now in its third year, the partnership results in the planting of 100 trees in Minnesota parks every time a Twins pitcher breaks the bat of someone on the opposing team. During the 2007 season, the pitchers broke 168 bats, resulting in 168,000 new trees planted!

The Lost Forty

Though Minnesota has very little virgin forest left, there’s a choice bit of acreage still in the Chippewa National Forest. This easily accessible land, “the lost forty,” is home to one of the last “old growth” sites of red and white pine in Minnesota. Some of the trees are 350 years old and between 22 and 48 inches in diameter. Here, the wild life includes bald eagles, hawks, red squirrels, weasels, and numerous other species.

Our gain is due to an oversight by early surveyors. In 1882 the federal survey crew led by Josiah A. King was finishing its work in the north woods. The chilly weather, the November winds, or the desolate swamp around them confused the men. They marked the 144 acres incorrectly, listing it as Coddington Lake, not the virgin pine wood that it was. So marked as water, the land went uncut by the logging companies. The acreage has since been declared a Scientific and Natural Area by the DNR. Take a virtual tour at the DNR site.

Did You Know?

- Colloquial names for white pine are old field pine, mast pine, cork pine, and soft pine.

- White pine came to Minnesota about 7000 years ago, following the last Ice Age.

- White pines were once so plentiful that a person could travel from the Atlantic Coast to Minnesota and seldom be out of sight of them.

- The trees’ blue-green needles are grown in bunches of five, making them easy to identify.

- White pine is a favorite of woodworkers because it is soft and easily painted or stained.

- It is a relatively long-lived tree—an average maximum age is probably over 500 years.

- Before logging began, white pine was found in every Minnesota county east of the Mississippi River from Minneapolis north to Canada.

- Minnesota’s largest white pine is 131’ tall, 180” in circumference and is found in Itasca County.

- The great white pine was The Tree of Peace to the Iroquois Nation. Its cluster of 5 needles signified the unification of the Five Nations (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca).

- Pine resin (sap) was used by several tribes to waterproof baskets, boats, and pails.

For more information see the 10 Plants That Changed Minnesota MSHS book.