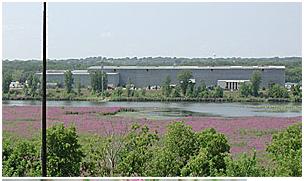

Beautiful, adaptable, hardy, fertile—all are words that describe the noxious invasive plant, purple loosestrife. Indeed, those attributes account for loosestrife’s rapid spread through Minnesota’s wetlands. It is found in 77 of the state’s 87 counties, primarily in streams, rivers, ponds, and wetlands. Once established, loosestrife stands are difficult and costly to eradicate. Minnesota has been particularly vulnerable because of its large number of wetlands. But thanks to biological controls with the beetles Galerucella pusilla and G. calmariensis Minnesota’s waterways are being cleared of the nuisance plants. A stand of purple loosestrife colonizing a pond.

Purple loosestrife came to North America from Europe in the early 1800s, most likely as ballast on ships. Seeds were embedded in the tidal flats of Europe. As seaman there shoveled the soil into the ships’ holds to add weight and stability for the ocean voyage, they inadvertently added the seeds. Once in port in America, the workers emptied the ballast to make room for cargo. The seeds of purple loosestrife float, enabling them to take hold along the Eastern shores. No doubt gardeners saw the pretty purple flowers and brought them home for their gardens. Also immigrants brought the plants over for medicinal and ornamental uses.

For 120 years the plant remained relatively dormant and caused few problems. Records show that in the 1920s several garden clubs in Minnesota planted purple loosestrife in the wetlands for “beautification.” The European strain may have bred with the native American lythrum plant, Lythrum alatum. This likely would have allowed new hybrid plants to develop favorable new gene combinations resulting in new, more robust plants with enhanced growth characteristics.

Purple loosestrife moved west across the United States and Canada, most likely as modern highways were built. The soil disturbance of construction and maintenance helped loosestrife to take hold in nearby drainage ditches and canals. Because of its appeal as a perennial garden plant, many individuals and nurseries helped it spread.

Once established, the plant can multiply quickly. It has an extended blooming season, allowing the plants to produce enormous quantities of seed, (about 2.7 million per plant, per year). Purple loosestrife is also quite efficient at spreading vegetatively, forming dense, impenetrable stands. In addition loosestrife seeds remain viable for up to five years. It is tolerant of many soil types (gravel, sand, clay or organic soil) and a wide range of environmental conditions (sunlight, pH, and temperatures). In North America it had no natural pest enemies. Taken together, all these factors enabled the plants to colonize an area speedily.

As it replaces native vegetation, wetland animals, including ducks, geese, toads, frogs and turtles lose their nesting sites, food sources, and cover. Many songbirds and fish depend on native plants. Because it reduces plant diversity, purple loosestrife has a negative impact on fish spawning and waterfowl life.

One of the Great Success Stories

Early in the 1980s the DNR along with concerned Minnesotans took note of the proliferation of loosestrife stands along the state’s many waterways. Several environmental and conservation groups organized a Purple Loosestrife Coalition in 1984. They approached the state legislature seeking to pass a law prohibiting the sale, transport, possession, or planting of purple loosestrife. That bill was tabled, but led to a new group of state and federal agencies (MnDNR, MnDOT, Mn Department of Agriculture, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service). This cooperative group made a study identifying the state’s risks by ignoring the problem and created a plan of action. In 1987 the state legislature passed a law making it a misdemeanor to sell purple loosestrife, L. salicaria. The Minnesota Commissioner of Agriculture designated the plant a noxious weed, which required landowners to remove or control the plants growing on their land.

In 1987 the DNR established the Purple Loosestrife Management Program, as a pilot program with a $196,000 biennial budget funded by LCMR. The program included a broad public awareness campaign, an inventory of purple loosestrife infestations, research into control methods, and recommendations. The first efforts included the use of herbicides to curb the stands. Over time, the DNR gradually reduced herbicide use, as biological controls became available. Now staff use the chemicals only on small and new infestations, which have a small seed bank.

Herbicide use in Minnesota on Purple Loosestrife

| Year | Money Spent | Amount Used |

|---|---|---|

| 1989 | $102,000 | 471 gallons |

| 2011 | $410 | .9 gallons |

Many individuals and nurseries had thought that the loosestrife cultivars they held were sterile ones and could not be problems for wild areas. However, research at the University of Minnesota showed that all the plants could cross with other loosestrife strains and grow quickly in the wild. As part of the education campaign, the DNR worked to persuade gardeners to remove the plant from home landscapes.

In the mid-1980s biologists began looking for biological controls and turned to Europe where the plant was kept in check by natural predators. The scientists focused on several insects to test intensely before releasing them on the loosestrife stands. Scientists at the University of Minnesota quarantined the insects for 10 years to make sure they would attack only purple loosestrife plants.

In 1992 the DNR released the first biological control agents, leaf eaters and root weevils. The insects that proved most successful in Minnesota were Galerucella pusilla and G. calmariensis. These leaf-eating beetles were hearty and able to withstand Minnesota winters. Richard Rezanka, invasive species specialist for the Northeast Region of the state, noted that one of the beetles, G. calmariensis performs better in the colder areas of the state; G. pusilla in the south. The DNR collect beetles from existing sites to move to new areas. “We now have tough insect stock,” Rezanka said, “and are expanding the biocontrol.”

At the larval stage, the beetles are stem burrowers, interrupting the water/food transport to the plants. As adults they chew on the leaves. The larval stage is the most destructive. In 2012 the DNR released 8,985,000 insects on 883 sites. The insects have made significant inroads into the purple loosestrife infestations. “This is one of the great success stories,” Rezanka explained. “Besides the biological controls, we have lots of volunteers out looking for purple loosestrife infestations. This has helped us reduce the populations across the state.”

Did You Know?

- The scientific name for purple loosestrife is Lythrum salicaria.

- The generic name, Lythrum, is derived from the Greek root for blood.

- Ancient herbalists noted its astringent and styptic properties.

- Tonics of the leaves, flowers, and roots were used to treat dysentery, healing of wounds and to staunch internal and external bleeding.

- A mature plants stands about 6-7’ high and 4’ wide.

- European garden books mention the beauty of the species far back into the Middle Ages.

- Nurseries sold purple loosestrife as an ornamental plant until 1987.

- The cultivar ‘Feuerkerze,’ ‘Fire Candle’ with rose-red flowers won the Royal Horticultural Society’s Award of Garden Merit.

- Purple loosestrife has been declared a noxious weed in 32 states.

- Naughty but nice, purple loosestrife pollen and nectar make delicious honey, with a unique flavor! Bees love the flowers.

For more information see the 10 Plants That Changed Minnesota MSHS book.